“He is my cross to bear,” exclaimed the mother of a wayward son. I drove home thinking about the conversation and wondered. How can we know for sure? Perhaps the situation is simply a function of living in a fallen world, the cumulative effect of poor decisions resulting in unpleasant consequences. On what basis can we say that a trial, such as this woman’s, is God’s particular calling to participate in Christ’s suffering? The fact that it is suffering is undeniable; but how is her situation related to the cross of Jesus? Furthermore, how can I extend pastoral encouragement to this dear woman to trust in God’s promises in the midst of her circumstances, to work it out theologically with a gospel focus?

For starters, we should remind ourselves of how suffering belongs to the Christian faith in the first place. With this connection in view, we can begin to reflect on how suffering relates to our experience. Here is how John Stott describes the situation:

Evangelical Christians believe that in and through Christ crucified God substituted himself for us and bore our sins, dying in our place the death we served to die, in order that we might be restored to his favor and adopted into his family.[1]

While it is one thing to confess this truth, it is quite another to live it out. In honest moments, we have to admit that we don’t immediately jump up and down with excitement when we think about carrying our cross. The cross of Christ means suffering and pain. Anyone who blithely promotes bearing it is either a masochist or out of touch with reality. You don’t need to experience a great deal of suffering to know that pain is not fun, which is why it’s called pain. Rooms with padded walls are constructed for people who think otherwise.

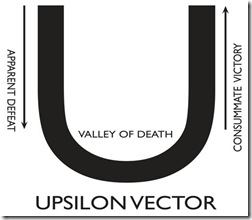

When I was in seminary I was teaching through Matthew’s Gospel at my church. My dear wife Angela, who was pregnant at the time, sat in the front listening to my lesson. In one of my classes I had been introduced to a concept which theologians call the “upsilon vector.”[2] Simply put, the vector traces the trajectory of Jesus’ life in terms of his descent into apparent defeat (dying on the cross) before ascending three days later in consummate victory (in the resurrection).

The upsilon vector is a wonderful theological truth, and I preached it with great zeal. However, at one point I looked at Angela’s robust belly and had a question cross my mind, “What if this child introduces suffering into my life? Will I apply the truth I am now proclaiming?” I swallowed hard and kept on teaching.

Two months later our first child was born. It was a boy. After being circumcised his site continued to bleed. It was shortly thereafter we learned of his condition called severe hemophilia. You can imagine what I thought of first—the upsilon vector. Now was my opportunity to apply it. It immediately became apparent, however, that the manner in which one descends into brokenness is not with confidence and strength. It’s with many tears, sleepless nights, and even depression. In Jesus’ words, “My soul is overwhelmed with sorrow to the point of death” (Mt 26:38).

Some Christians would respond saying that God doesn’t want us to have sickness and disease. We must claim healing which is what God desires for us. I wish this were so, especially when I struggle to stick an intravenous needle into my son’s tiny veins. But alas, it’s not. The health-and-wealth gospel is fundamentally flawed because it fails to understand the cross of Jesus.[3] It fails to recognize that the cross was not only an instrument of torture on which God’s Son died, it’s also the pattern to which our lives must be conformed. Again, I quote from John Stott:

Every time we look at the cross Christ seems to say to us, “I am here because of you. It is your sin I am bearing, your curse I am suffering, your debt I am paying, your death I am dying.” Nothing in history or in the universe cuts us down to size like the cross. All of us have inflated views of ourselves, especially in self-righteousness, until we have visited a place called Calvary. It is here, at the foot of the cross that we shrink to our true size.[4]

The cross instills brokenness and humility. Despite its heaviness and rough texture, we bear it by faith, patiently waiting for “the redemption of our bodies” (Rom 8:23-25). And just when you expect to drop dead beneath its weight, God provides empowering grace. As Paul the Apostle wrote to the church at Corinth:

But we have this treasure in jars of clay to show that this all-surpassing power is from God and not from us. We are hard pressed on every side, but not crushed; perplexed, but not in despair; persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed. We always carry around in our body the death of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body….Therefore we do not lose heart. Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day. For our light and momentary troubles are achieving for us an eternal glory that far outweighs them all. So we fix our eyes not on what is seen, but on what is unseen. For what is seen is temporary, but what is unseen is eternal (2 Cor 4:7-11; 16-18).

Now that my son is nine years old, I can tell you without reservation that Angela and I have experienced dimensions of God’s power on account of his hemophilia. This pattern of cruciform love has produced strength through weakness and joy from sorrow.

For what it’s worth, this is how I think about whether a circumstance properly belongs in the category of “cross-bearing.” I ask this question: How does this trial present opportunity for me to advance the gospel of Jesus Christ? Of course, every situation is full of such potential. Our response to trials is what matters, seeing them not so much as hurdles which must be cleared but as catapults that propel the message of Christ forward. Suffering is cross-bearing when it serves the cross, when our strength is diminished and God’s power is made perfect. This is how the world sees the reality of Christ.

[1] John Stott. The Cross of Christ. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1986, 7.

[2] Dr. Royce Gruenler is the scholar whom I recall first using the term upsilon vector.

[3] Richard Bauckham says it well in his book God Crucified: Monotheism and Christology in the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. 1998, 46, when he writes, “In other words, we must consider Jesus as the revelation of God. The profoundest points of New Testament Christology occur when the inclusion of the exalted Christ in the divine identity entails the inclusion of the crucified Christ in the divine identity, and when the Christological pattern of humiliation and exaltation is recognized as revelatory of God, indeed as the definitive revelation of who God is.”

[4] John Stott, The Message of Galatians (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1968), 179.