Since writing Holy Ground, I have enjoyed following several Catholic authors and journalists in an attempt to remain current on Catholic issues. One such writer is Philip Lawler, editor of Catholic World News (cwnews.com). Phil recently described the Catholic identity of Ted Kennedy from the late senator’s autobiography titled “True Compass: A Memoir.” In the following excerpt, Phil presents Kennedy as a classic example of what I have titled the “Cultural Catholic.”

Since writing Holy Ground, I have enjoyed following several Catholic authors and journalists in an attempt to remain current on Catholic issues. One such writer is Philip Lawler, editor of Catholic World News (cwnews.com). Phil recently described the Catholic identity of Ted Kennedy from the late senator’s autobiography titled “True Compass: A Memoir.” In the following excerpt, Phil presents Kennedy as a classic example of what I have titled the “Cultural Catholic.”

Kennedy mentions his Catholicism hundreds of times in this book, but almost invariably he is referring to the cultural heritage of Catholicism rather than to its doctrinal content or its spiritual exercises—the form rather than the substance of his faith. Still he insists that his faith shaped his political outlook. In one of the book’s most revealing passages, he relates how his thoughts matured as he entered adult life:

“My own center of belief, as I matured and grew curious about these things, moved toward the great Gospel of Matthew, chapter 25 especially, in which he calls us to care for the least of these among us, and feed the hungry, clothe the naked, give drink to the thirsty, welcome the stranger, visit the imprisoned. It’s enormously significant to me that the only description in the Bible about salvation is tied to one’s willingness to act on behalf of one’s fellow human beings.”

It boggles the mind that an adult Catholic—who presumably heard the Scriptures read at every Sunday Mass, even if he never read the Bible himself— could claim that there is only one passage in the Bible addressing the question of salvation. But the above quotation contains another sign, less obvious but even more telling, of the author’s detached attitude toward his faith. When he says that “he calls us to care for the least of these among us,” Kennedy never identifies who “he” is. The name of Jesus does not appear anywhere in this memoir.

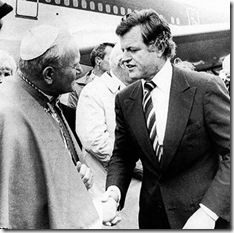

“All of my life, the teachings of my faith have provided solace and hope,” Kennedy wrote as he faced the prospect of death. He surely did draw solace from his faith, but not guidance. He knew that the Church offered words of comfort; he never recognized that the Church also spoke with authority. So in his final illness, while he felt the need to write to Pope Benedict XVI, asking for the pontiff’s blessing, he still saw no need to renounce his long history of public opposition to Church teaching on the dignity of life.

A Christianity without Jesus, a Catholicism without sacraments, a doctrine without authority: this is the conception of the Church that emerges from True Compass. Ted Kennedy saw Catholicism as an important part of his identity, of his family history, of his cultural patrimony. But his life story provides very little evidence that his faith shaped his political ideals. On the contrary, it seems clear that his political ideals shaped the content of his faith. The story of Ted Kennedy’s public life is, to an alarming extent, the story of a generation of Catholics—in Boston in particular, in America in general. It is, regrettably, not a story of how these Catholics shaped the popular culture, but of how that culture changed their faith.