I am currently reading one of the most enjoyable books I have read in years. It is titled Brand Luther: How an Unheralded Monk Turned His Small Town into a Center of Publishing, Made Himself the Most Famous Man in Europe—and Started the Protestant Reformation, by Andrew Pettegree. How is that for a subtitle? I suppose this is right up my alley as lover of theology and one who grew up in a family-owned printshop. I intend to share some highlights from this work in the coming weeks. For now, however, I will present a particular point that appears throughout its pages.

Pettegree, who is professor of history at the University of St. Andrews and founder of the St. Andrews Reformation Studies Institute, explains how God’s word persuades the church toward faithfulness, that is, how people become committed to distinctively Christian living. As he explains in the following quotation from another of his books, Reformation and the Culture of Persuasion, the activation of faith is fueled by the distribution of the Bible, an initiative that burgeoned in the sixteenth century Reformation and continues to the present. For all the differences that have unfolded over the last 500 years, it’s remarkable how similar is the persuasive power of God’s Word. While the decisive force is the operation of the Holy Spirit, there is something about the text itself that commands our attention. In Pettegree’s words:

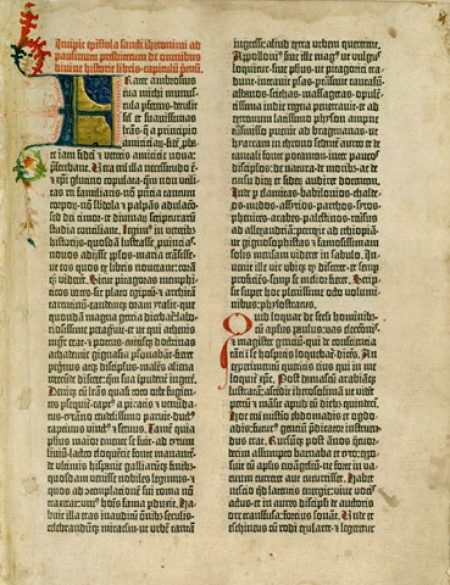

[I]t is hard in any survey to do real justice to [the Bible’s] primacy and influence. But this was a remarkable and many-faceted book, a success in so many of the categories of print that sixteenth-century readers found so fascinating. It was a travelogue and a work of history; a work of literature and poetry; it provided the model for much of the most successful drama of the age; it was a work of prophecy in an age obsessed by prophecy; it was a treasure trove for botanists, grammarians and etymologists, and a foundation text for students of the ancient languages; it was a work of jurisprudence, perhaps the sixteenth century’s most influential legal text; it was certainly the century’s most influential work of political thought. It provided role models for rulers and priests, for fathers and mothers, for soldiers and martyrs.

In this book the print culture of the sixteenth century was displayed in all its technical sophistication. It could be a handy pocket-sized book in tiny print, or a gloriously illustrated folio. The narrative illustrations in the Old Testament brought to life some of the greatest stories of the Christian tradition; even in the austere purged editions of the later Protestant tradition the text often came accompanied by maps, technical drawings, and ingenious diagrams of belief and unbelief. It is not too much to say that in this one volume is epitomized much of what sixteenth-century book culture had to offer.

The sixteenth century placed this compendious and many-sided work directly in the hands of unprecedented numbers of people. Throughout the century and in all European vernaculars there were published at least 5,000 whole or partial editions of the Bible, a total of at least 5 million copies.1

Footnotes:

1 Andrew Pettegree, Reformation and the Culture of Persuasion (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 191.