Swords flashed in the sun as an agitated mob of peasants pressed against the doors of the Geneva Senate House. Fearing for their lives, the ruling Council of Two Hundred had barricaded themselves inside the building, though they could still hear the shouts of the crowd calling for the death of the city’s pastor, John Calvin. By all appearances, the situation was out of control; December 16, 1547, promised to be a bloody day. Just as the frenzy reached a fever-pitch, however, Calvin himself appeared behind the mob in the great hall. He called for their attention, and the people turned to face him. No one attacked; they only stared in silence at their defenseless pastor, his arms folded. Calvin walked slowly into the middle of the crowd and, baring his chest, shouted, “If you want blood, there are still a few drops here! Strike then!”1 No one raised a hand, and the Reformer ascended the steps and turned to address the crowd. Deeply affected by his exhortation, the people embraced one another, lowered their weapons, and departed in silence.

Sixteenth-century morals were generally loose, but Geneva seems to have been even worse than most. Riots were frequent and bloody, and where other towns merely looked away from such sins as drunkenness and prostitution, Geneva had actually regulated them. Taverns were established and overseen by the town council, and a portion of the city had even been set apart for prostitutes to conduct their business. Convinced by William Farel in 1533 to help reform the city, Calvin began his work in earnest.

The first changes were effected with little opposition, concerned as they were with establishing Protestant doctrine. In 1538, however, Calvin proposed a biblical church discipline. Many in Geneva were incensed. No longer were the reforms merely ecclesiastical; now the pastor was trying to reform their lives. The city council declined to enact the plan and finally exiled Calvin when he refused the Lord’s Supper to some profligate people. He retired to Strasbourg until 1542, when a delegation arrived from Geneva, inviting him to return.

The Reformer grudgingly accepted but demanded concessions, including the right of the Church to excommunicate. Nevertheless, opposition soon rose again, this time from a party aptly known as the “Libertines.” Led by the Captain-General Ami Perrin, they chafed at Calvin’s intrusion into their wanton, lawless lives. How could this pastor refuse them the Lord’s Supper merely because they lived in a drunken, fornicating stupor? One of their number, Jacques Gruet, attached a vulgar placard to Calvin’s pulpit, threatening him with death if he did not “shut up.” An investigation of Gruet’s house turned up a cache of heretical writings, and the town council did what any sixteenth-century European government would have done in such a case. They had Gruet arrested, tried him for heresy, and beheaded him in July of 1547.

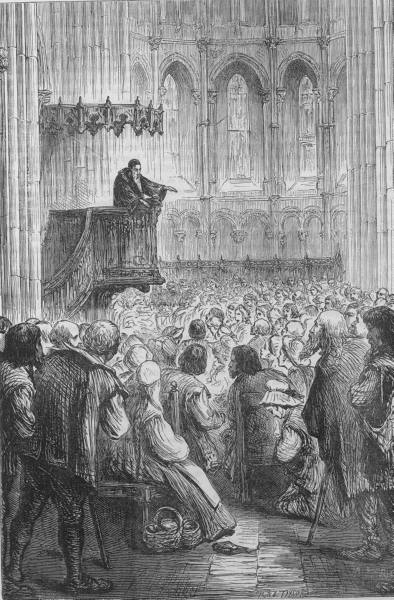

Peace ensued for some months as the Libertines licked their wounds. Calvin went on preaching four times a week from his pulpit at St. Pierre, but soon, Perrin hatched a new plot to overthrow the Reformer, this one in league with the Duke of Savoy. When the city council got wind of it, they stripped Perrin of his position. The Libertines took up their swords in Perrin’s defense, converging in the courtyard of the council chamber. Calvin happened to be walking along a nearby street when he heard the commotion. Rounding the corner into the courtyard, he was confronted by a bloodthirsty mob demanding his death.

John Calvin faced his opponents with undaunted courage. Refusing to give in to their demands, he walked among them—even as they screamed for his blood—and exhorted them to holiness from the Scriptures. People are always willing to hear preaching so long as it does not call them to change their lives. Faithful, biblical preaching, however, which boldly confronts sin with the Word of God, will often be fiercely opposed.

Footnotes:

1 Philip Schaff, History of the Reformation, in History of the Christian Church, vol. 7, 5th ed. revised (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1907), 508.